How Good Really Was FiveThirtyEight’s Soccer Power Index?

A Seven-Season Reality Check Against Pinnacle’s Closing Odds

Hi friend,

FiveThirtyEight has always had a kind of mythic status in the football world. Their Soccer Power Index (SPI) was one of the first “super-model” rating systems I stumbled upon when I began my own analytics journey. And for years — before it was shut down — SPI became a reference point for pre-game probabilities and end-of-season title chances across football Twitter.

Last week, I came across a historical dataset that included SPI’s match-by-match outcome probabilities. Naturally, the first question that came to my mind was:

“If someone blindly trusted SPI for years… would they have made money?”

And that curiosity brings us to today’s issue.

Welcome to The Python Football Review #019.

In this edition, we’ll explore how much one would have won (or lost) over seven seasons by betting strictly according to SPI’s implied probabilities — and we’ll compare those numbers to the sharpest odds in world football: Pinnacle’s closing line.

As always, the Python notebook is included at the end so you can replicate everything yourself from scratch (and mock my results).

Let’s get into it.

A Few Words About the Data

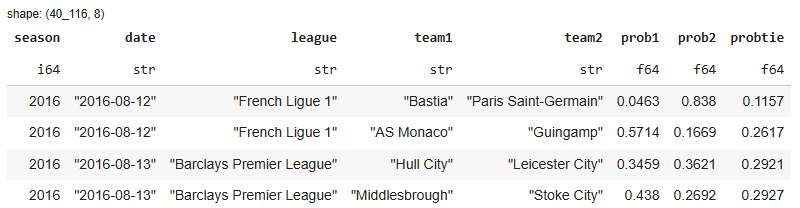

The historical SPI dataset — available on Kaggle — includes 40 leagues (male and female, national and international) covering the 2016/17 to 2022/23 seasons. For every match, we have SPI’s estimated probability of home win, draw and away win as illustrated below.

From these probabilities we’ll compute fair odds simply by taking the inverse. For example, SPI gave Bastia a 4.63% chance of beating PSG in the opening match of 2016/17. The corresponding odds according to FiveThirtyEight are therefore 1 / 0.0463 = 21.6 which means that if you bet 1€ on that outcome, you would have won a total of 21.6€ back (in case if a winning wager of course).

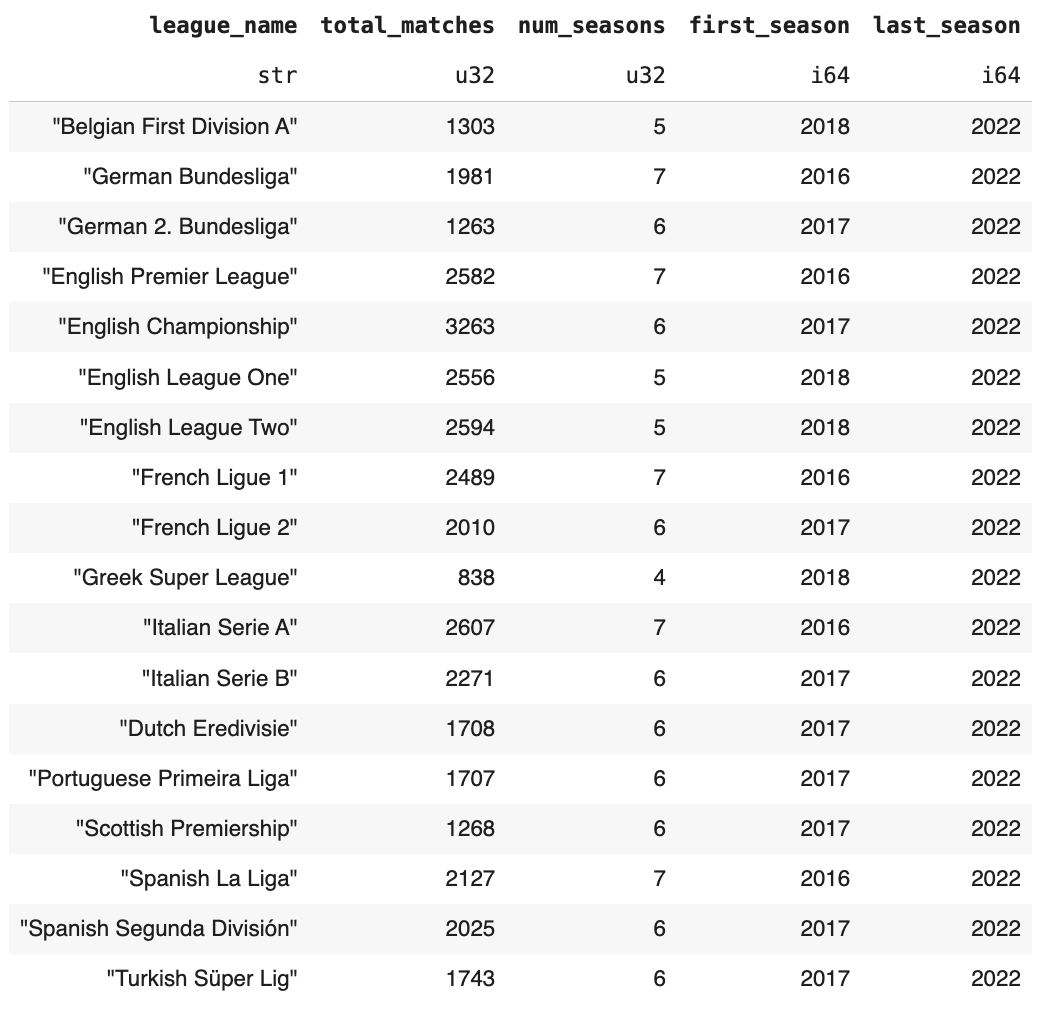

To analyse profitability, I then needed the market odds for each match. Based on ease of downloading, I downloaded the market odds for 18 of those 40 leagues (my newsletter, my rules), which is still a very healthy sample.

The odds data comes from Joseph Buchdahl’s football-data.co.uk, as usual. For market prices, we take Pinnacle closing odds, because: If your system consistently beats Pinnacle’s closing price, you almost certainly have an edge.

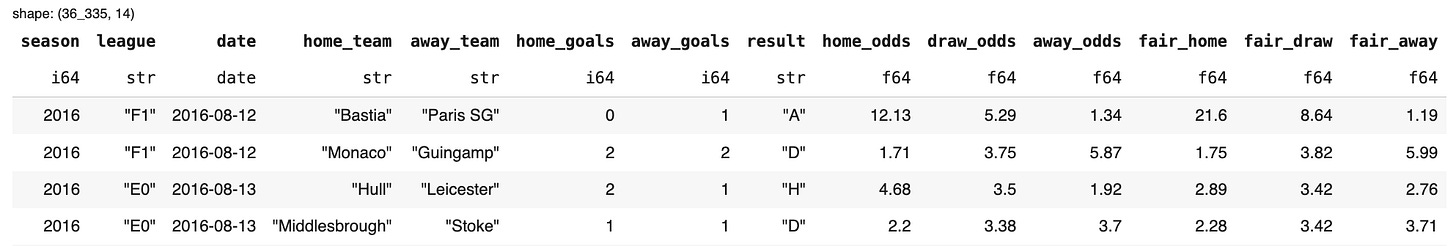

After matching team names across the two datasets, we end up with 36,335 matches. And here is what the final analysis table looks like:

fair_home,fair_draw,fair_away→ from SPIhome_odds,draw_odds,away_odds→ Pinnacle closing odds

Here’s the overall coverage.

The Betting Simulation

For each match, we look for value. A value bet exists when Market odds > Fair odds.

Simple example: In Bastia vs PSG, SPI assigns PSG fair odds of 1.19, while Pinnacle offers 1.34. That’s a 12.6% value edge ((1.34/1.19) -1), which means — in theory — we’d place a bet on PSG. To avoid over-exposure, we place only one bet per match, even if multiple outcomes show theoretical value. For each bet we will place a single unit wager.

So to recap: we’re about to test 36,335 matches across 7 seasons and 18 leagues. We’ll compare SPI’s fair odds to Pinnacle’s closing odds and look for value. Whenever value appears, we place a single 1-unit bet on the outcome with the highest positive edge.

And the question is: What would the profitability look like? Would SPI beat the market? Or would it behave like a very polite random walk?

Let’s find out.

Simulation Results

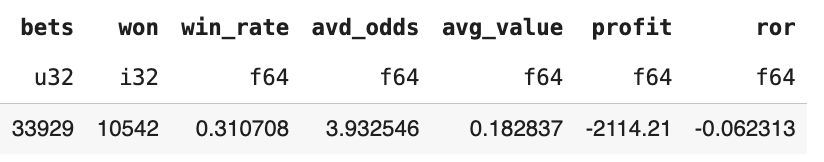

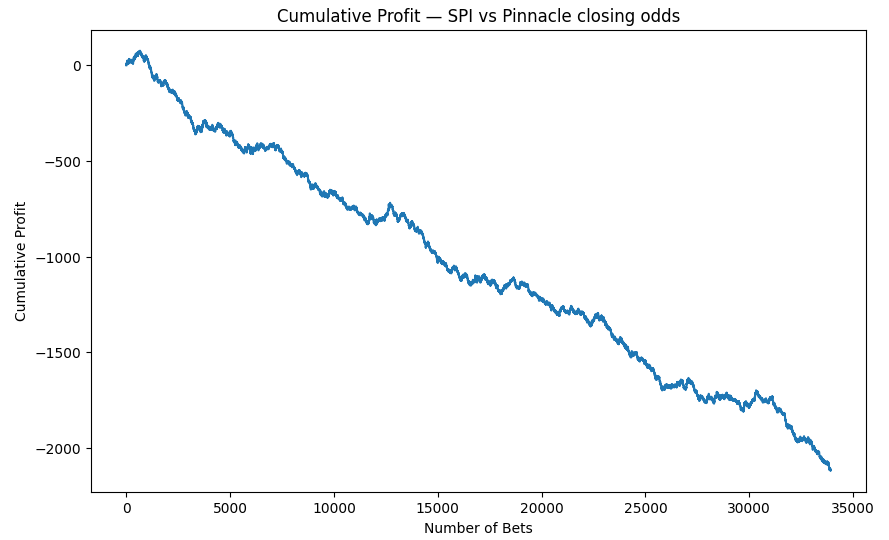

Over the full period, the model would have generated 33,929 bets, each taken when the SPI-implied probability appeared higher than Pinnacle’s market probability.

Across these bets, the average perceived value was around +18.2% (that’s a lot), and the system achieved a 31% win rate.

However, despite the perceived positive expected value, the long-term outcome was a net loss of about 2,114 points, corresponding to a –6.2% rate of return. In practical terms:

For every €100 placed, you’d expect to lose about €6.

Can the results be improved? Of course. There are dozens of data mining filtering techniques we could explore, such as:

restricting to lower odds (more likely events)

betting only when value exceeds certain thresholds — or avoiding extreme value outliers (model/market mistakes)

focusing on home-only strategies (or excluding draws)

applying Kelly-criterion staking

These could change the curve and potentially improve performance.

But the general conclusion is :

A naïve, blind strategy that follows SPI as a pricing model would lose money against Pinnacle.

Is this surprising? Not really.

No one ever claimed SPI was designed for betting. And importantly, we used Pinnacle closing odds, widely considered the sharpest lines in the world.

And SPI—at its core—is:

a static pre-game index

ignoring late team news & therefore blind to injuries, squad rotation, fatigue, travel, and line-up announcements

accessible to everyone well in advance.

Meanwhile, Pinnacle’s closing line:

reflects the aggregated knowledge of the sharpest bettors

adjusts dynamically until the final seconds before kickoff

incorporates global betting pressure

reacts instantly to breaking news

So would it be surprising if a static, pre-game, publicly available rating system consistently beat the closing line of the sharpest bookmaker in the world?

No — exatly the opposite would be suprising.

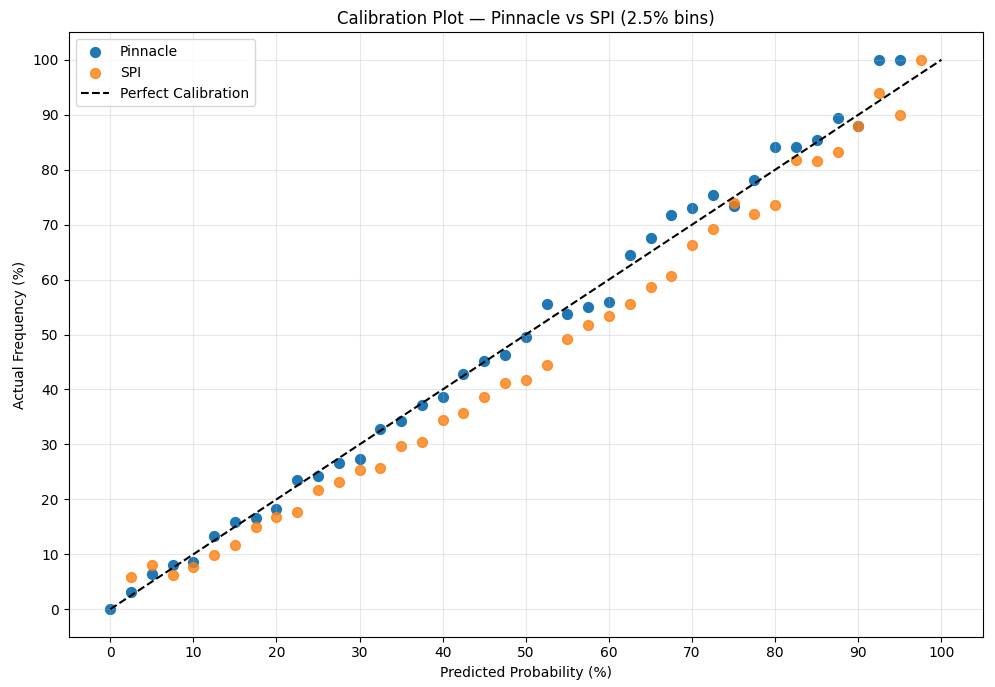

Having said that, here’s how SPI’s predicted probabilities fared against the actual results. In the chart below, we compare SPI’s probabilities to those implied by Pinnacle’s closing odds, and we check how well each aligns with reality.

A perfectly calibrated model would sit right on the dashed 45° line — meaning that events predicted at 30% really happen 30% of the time, 60% events happen 60% of the time, and so on.

Pinnacle (blue) is (for the most part) almost glued to that line. This is exactly what you’d expect from the sharpest bookmaker in the world. Their odds, once binned at 2.5% intervals, map extremely closely to actual match outcomes. When Pinnacle says something is 70% likely, it really is about 70% likely.

SPI (orange), however, shows consistent patterns of miscalibration:

At low probabilities, SPI underestimates the probabilities— for example events it predicted at 5% happened around 9% of the time.

Across most of the range (10–90%), SPI systematically overestimates true frequencies — for example, matches it rated at 50% actually occurred only 41% of the time.

At high probabilities (90–100%), SPI becomes too conservative again, assigning lower win chances than what actually happened on the pitch.

In simple terms: SPI gets the direction right, but the confidence wrong.

It knows which team is stronger, but it consistently misjudges by how much. And this miscalibration is exactly why betting strictly on SPI’s probabilities — without adjustments — fails to beat Pinnacle. Pinnacle isn’t just predicting winners; it’s capturing the true likelihood with remarkable precision.

A broader reminder

This little experiment highlights an important point: even well-constructed “super-computer” models have limits. FiveThirtyEight’s SPI was analytically strong, but that doesn’t automatically translate into beating the sharpest sports betting markets on a match-by-match basis — and it was never designed to.

End-of-season simulations, title probabilities, and playoff chances were always where SPI shined. These tools are incredibly valuable for understanding long-term dynamics, but they are still just simulations. They don’t replace real-time information, market pressure, or closing-line pricing.

And to be clear: SPI was useful — very much so.

It consistently captured directional team strength, meaning it generally understood who the stronger and weaker sides were based on recent performance. It was also transparent in how it was built (combining xG and non-shot xG), which allowed you to adjust ratings yourself. If you felt a team was over- or under-performing those metrics you could mentally nudge the probabilities up or down.

So no, SPI couldn’t beat Pinnacle’s game-by-game closing odds. But that’s an unrealistic benchmark for any static pre-game public model.

What SPI did provide was a solid, interpretable foundation — a starting point for reasoning about team quality, season trajectories, and long-term probabilities. And for most fans, analysts, and hobbyist forecasters, that is already incredibly powerful.

Boom — that was FiveThirtyEight vs Pinncle.

This was a fun exercise, even if I’m a little disappointed the curve ends well below zero. I honestly expected something slightly closer to breakeven.

But maybe that’s the next step — building a more refined, bottom-up forecasting model that incorporates last-minute news and seeing whether that can close the gap.

If you want to reproduce the results yourself, the code is available below.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end.

See you next week,

Martin